I visited Uzbekistan in August 2023, as part of my Central Asia trip with a good friend from college, Allen Liu. I visited three cities with Allen (Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara), then I continued on my own to Khiva, Urgench, Nukus, and Moynaq in the nation’s northeast on my own. Uzbekistan is a desert country with a rich cultural history, that remains relatively undiscovered by Western tourists. Because we visited during the scorching summer, there were even fewer tourists than usual. I was surprised that almost all cars were white Chevrolets. I suspect that the white color reflects sunlight and hides desert dust that no doubt gradually accumulates on them over time. A highlight of my trip was seeing Uzbekistan’s Zoroastrian heritage – an ancient Iranian religion that was dominant in the region before the spread of Islam. It also happens to be the religion of my father’s side of the family. Many mosques in Uzbekistan used to be Zoroastrian fire temples, and it was fascinating to see the vestiges of this religion’s culture and architecture. I also really enjoyed talking with the kind manager of the Avesta Museum in Urgench, who patiently showed me an exhibit on Uzbekistan’s Zoroastrian history despite his not speaking English, and my not speaking Russian or Uzbek.

Tashkent is Uzbekistan’s capital and largest city, located right next to the border with Kazakhstan. It features an interesting mixture of modern-looking buildings and historic Uzbek architecture. Samarkand is Uzbekistan’s third largest city, its tourist hub, and the ancient capital of the Timurid Empire. This is a stunning city, with some of the most beautiful architecture I have ever seen. I describe it to friends as being like Paris or Rome, but at a third of the price and with a quarter of the tourists. Bukhara is Uzbekistan’s seventh largest city, and is slightly less touristic than Samarkand, but consequently feels even more authentic. On top of its many mosques and madrasas, the Ark of Bukhara is an impressive fortress that dominates the city. All three of these cities were key nodes on the historic Silk Road, and Uzbekistan’s excellent train system connects them via high-speed rail, so it was easy to get from one to another.

Uzbekistan, like its Central Asian neighbors, succumbed to the Mongol invasion in the 13th century. As the Mongol Empire split up, Amir Timur took control of the region. Because he was not a direct descendant of Genghis Khan, Timur could not call himself a khan (a formal title for a ruler), so he initially ruled through a puppet leader. He started the Timurid Empire, which he led between 1370 and 1405. Uzbekistan idolizes Timur for his military genius as an undefeated general who rapidly expanded his empire’s size. He was a brilliant strategist, winning victory through unorthodox means. He managed to take over the Delhi Sultanate using camels loaded with hay, which he set on fire, as sacrificial frontline soldiers. The blazing camels scared the defendants’ war elephants and caused them to panic, disrupting their defensive positions. However, outside of Central Asia, Timur is remembered for the brutality and cruelty of his forces, which slaughtered millions of people. After the Timurid Empire, the region was controlled by the Bukharan, Khivan, and Kokand Khanates, which lasted until the Russian Empire gradually took them over in the late 1800s and early 1900s. After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Uzbekistan became part of the Soviet Union.

After gaining independence from the USSR in 1991, Uzbekistan was ruled by Islam Karimov, and autocrat whose regime committed many human rights abuses. Prominent among these is the 2005 Andijan Massacre, where the Uzbek National Security Service slaughtered hundreds of people protesting the arrests of two dozen local businessmen. Like his Kazakh compatriot Nursultan Nazarbayev, Karimov’s cult of personality remains visible in Uzbekistan’s National Museum, where a whole exhibit is dedicated to showing his shaking hands with world leaders. After Karimov’s death in 2016, Shavkat Mirziyoyev became president. Although Mirziyoyev retains many of Karimov’s autocratic tendencies, he has opened Uzbekistan towards the outside world and liberalized the country through various policies including abolishing the death penalty. He also formally changed the Uzbek alphabet to follow a Latin script, instead of the Cyrillic script that was mandated during the Soviet period. This makes Uzbekistan slightly easier to navigate than its neighbors in Central Asia for Western tourists.

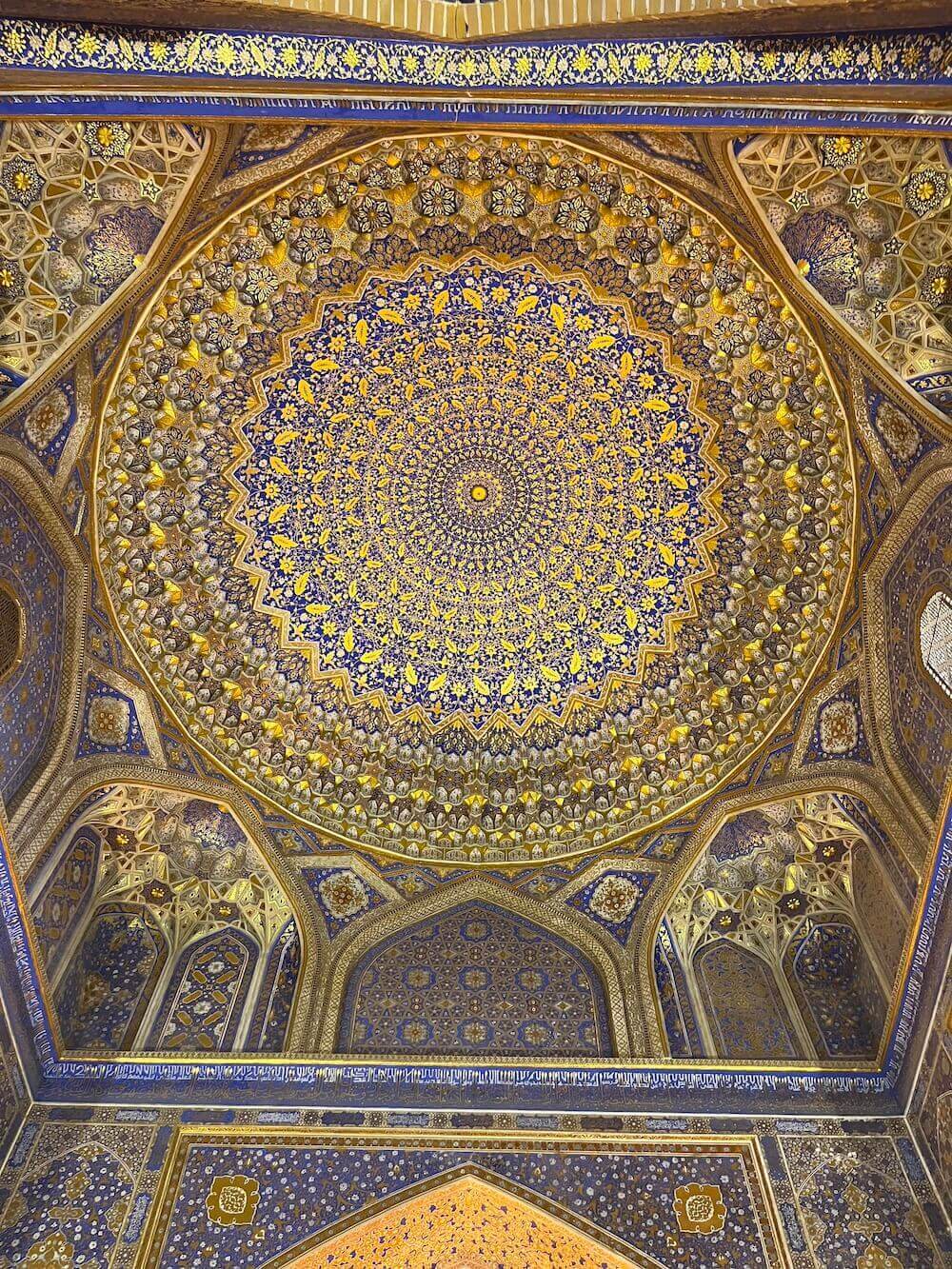

Uzbekistan’s most famous touristic location is Samarkand’s Registan (which means desert in Persian). This central square is surrounded by three massive madrasas, each of which is built in Uzbekistan’s ornate architectural style. Although Westerners usually associate madrasas with religious institutions, the term simply means school, and Samarkand’s madrasas also taught political officials, mathematicians, and lawyers. One of these buildings was built by Ulug Beg, a sultan who ruled the Timurid Empire between 1447 and 1449. He was most remembered for being a brilliant astronomer and mathematician, who made significant advances in trigonometry and built a cutting-edge (for its time) observatory that made Samarkand a center of science and astronomy. Schools in the West make it seem like all major scientific advancements originated in Europe; it was eye-opening to realize just how advanced 15th century Uzbek science and astronomy was.

The historic town of Khiva is in Uzbekistan’s northwest. Along with Bukhara, it used the be the center of Central Asia’s slave trade, which was only abolished after the Russian Empire’s invasion of the region in 1873 prompted a slave rebellion. Khiva’s walled city center (called the Itchan Kala) somehow has retained its historic architecture despite a century of Russian and Soviet rule, and today the entire center is a UNESCO World Heritage site. The city has countless mosques, mausoleums, and madrasahs that are built in classic Uzbek style, and the 44m tall Islam Khoja minaret offers a stunning view of the entire city. Because Khiva is far away from Uzbekistan’s capital (though still easily accessible by night train), it attracts relatively few tourists and feels very authentic.

The Aral Sea used to be the world’s third largest lake. Starting in the 1960s, the Soviet Union began intensively cultivating cotton in Central Asia and diverted the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers that fed into it. Over the next few decades, the Aral Sea shrunk to 10% of its original surface area, in one of the world’s worst environmental disasters. This had a devastating effect on the local economy – the town of Moynaq used to be one of the largest contributors to the USSR’s fishing industry, but today this fleet of once-proud ships lies as a skeletal remnant of its former glory. To get to the Aral Sea, I had to take a night train from Samarkand to Nukus, which was surprisingly comfortable. From here, the tour guide picked me up and we drove for three hours to Moynaq. Then, after a four-hour drive over the Aralkum Desert (the old seabed of the dried-up lake), we finally reached what is left of the sea. Driving over the flat lakebed for hours was unsettling, and made me realize just how serious an ecological disaster this was.