I visited Kazakhstan in July 2023, as part of my Central Asia trip with Allen Liu, a good friend from university. I flew to Astana after spending a week in the United Arab Emirates. After enduring the open-air saunas that are Dubai and Abu Dhabi, with temperatures consistently in the high 40s Celsius / 110s Fahrenheit, Astana felt like a temperate paradise. At the airport, the taxi driver I approached asked for 15,000 tenge (around $30), but I had been warned that foreigners are frequently ripped off, so I negotiated it down to 4,000 tenge ($8). After two days in Astana, I took a 2-hour flight to meet Allen in Almaty. Kazakhstan is perhaps the single least vegetarian-friendly place I have visited – more than once I could not find a single meatless dish on the menu, even including soups and salads.

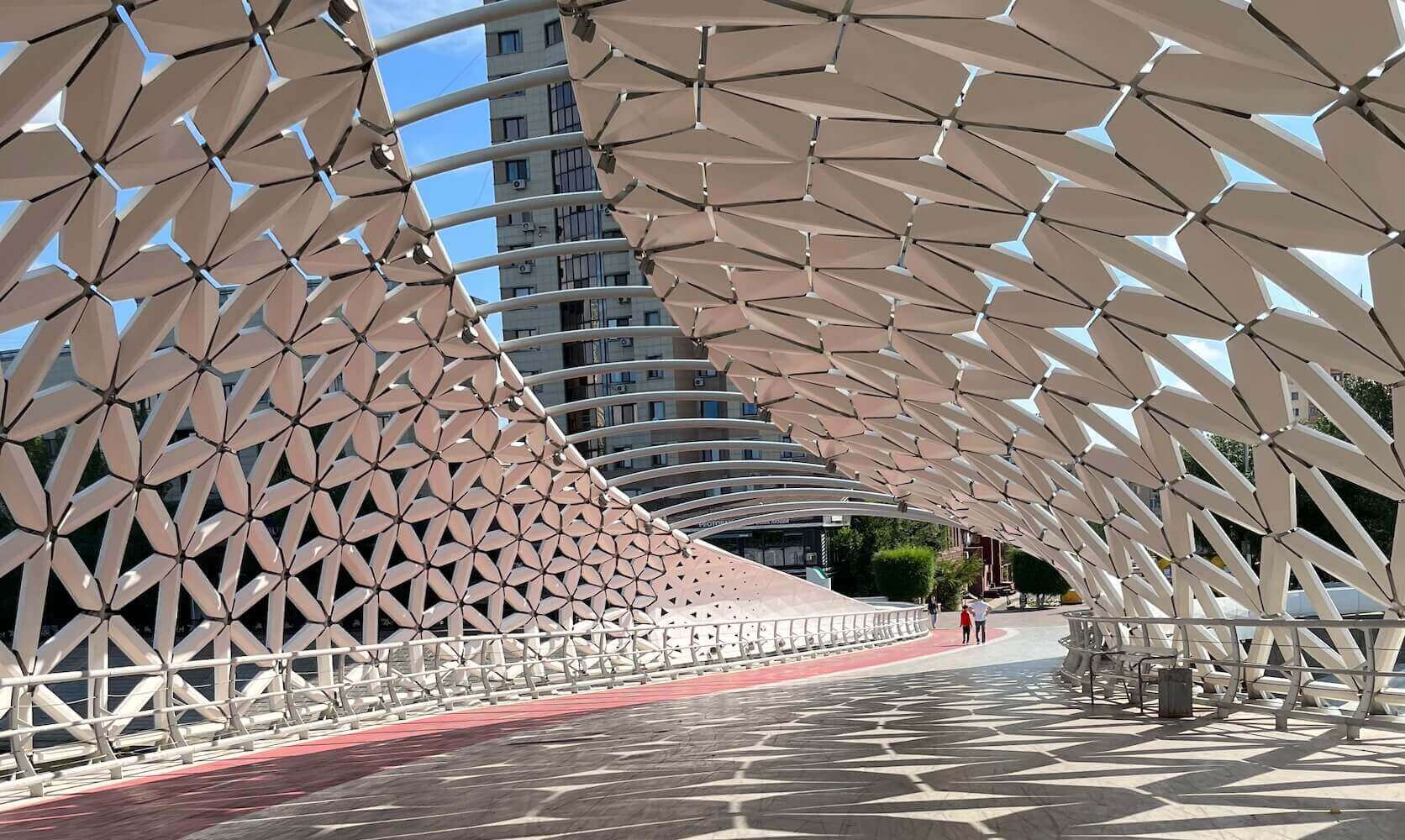

Almaty and Astana are two cities that differ in every way imaginable. Almaty is Kazakhstan’s largest city and economic center. Its minimalist Soviet architecture is embellished by the many trees that decorate the city. It is in the south of Kazakhstan, next to the massive Tien-Shan mountains. Almaty was the nation’s capital until 1997, when the Kazakh government decided to shift the political center to Akmola, which was renamed a year later to Astana. The Kazakh government hired Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa to design the city, and he chose to integrate many modern and even futuristic designs in the new buildings and structures. For example, the Baiterek is a 105m tall observation tower inspired by a Kazakh myth about a tree of life. Astana felt like it could be the scene of a sci-fi movie set several decades in the future. It certainly was not what I expected from a country many people in the West have never even heard of. Astana is in Kazakhstan’s north steppes, so the terrain around the city is perfectly flat as far as the eye can see.

The Kazakh people have traditionally been nomads and are of Turkic origin. The region was taken over by the Mongol Empire’s rapid expansion under Genghis Khan in the 13th century. After his death, the Mongol Empire split in four, and Kazakhstan fell under the control of the Golden Horde, a vast khanate whose territory ranged as far east as Ukraine. The Golden Horde split up in the mid 15th century, and its successor state in Central Asia was the Kazakh Khanate, which would rule the area until the mid-19th century, when it was taken over by the Russian Empire.

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, Kazakhstan was integrated into the Soviet Union. The Kazakh Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic suffered particularly badly from the Soviet Famine of 1930-1933. The USSR’s policy of collectivized agriculture forced many Kazakhs into farms that went contrary to their historically nomadic way of life. In 1930, an especially cold winter killed much of Kazakhstan’s livestock, while the Soviet governor Filipp Goloshchyokin requisitioned large numbers of animals from Kazakh farmers. This resulted in over a million deaths – around 35% of the region’s population. Ethnic Kazakhs were affected worse than Russians, and by the end of the famine Kazakhs were no longer the majority ethnic group in their own territory. Kazakhstan remained part of the Soviet Union until its independence in 1991.

Astana’s Grand Mosque is one of the largest mosques in the world. It was completed in 2022, and like the rest of Astana, its design feels very modern. Kazakhstan has a Muslim majority but, after decades of Soviet repression and a lack of religious freedom, the nation has developed a very secular approach to religion. The government seems eager to promote religious tolerance. In 2006, it created the Palace of Peace and Reconciliation, a giant 62m tall pyramid that serves as the meeting point for the Congress of Leaders of World and Traditional Religions. The pyramid contains exhibits on many influential world religions including Islam, Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, and Buddhism. Since there were no other English-speaking tourists around when I was there, I got a free private tour of the place, and enjoyed seeing how a country can honor and respect multiple religions without preferencing one over another.

The first thing you see in the Kazakhstan National Museum is a giant golden steppe eagle, a symbol of Kazakhstan that appears on the country’s flag. One of the most eye-opening exhibits of the museum was a section dedicated to its political leaders. Between its independence in 1991 and 2019, Kazakhstan was led by Nursultan Nazarbayev, who ruled the country as a dictator, and set up an elaborate cult of personality. The museum exhibit featured several walls plastered with pictures of Nazarbayev shaking hands with other prominent political figures from around the world, seeming to show how much he had done for his country. In 2019, Nazarbayev resigned, and was succeeded by Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, who initially continued Nazarbayev’s policies, and announced that the capital city would be renamed from Astana to Nur-Sultan in his honor. However, he has since split with Nazarbayev, stripping him of some of his post-presidential special privileges, and changing the capital’s name back to Astana. Tokayev seems to be loosening Nazarbayev’s authoritarian system, though Kazakhstan remains very far from a free democracy.

The Monument of Glory in Almaty commemorates 28 Soviet soldiers led by Ivan Panfilov, a Russian general who fought for the USSR against the Germans during World War II. In November 1941, the Nazis were rapidly advancing on Moscow and were less than 100km away. Panfilov’s division of Kazakh and Kyrgyz soldiers allegedly held back the German advance and destroyed 18 German tanks, before Panfilov and his 28 guardsmen were killed. This story is likely to have been exaggerated, as the USSR needed heroic stories to motivate its citizens to join the war effort, and several of the 28 guardsmen who were supposedly killed turned up alive in the Soviet Union years later. Nonetheless, the legend remains inspiring, and the statue illustrates the Soviet Union’s determination and resilience in defending itself from a far better equipped enemy. It also alludes to how the USSR persuaded many of its citizens to fight in a war thousands of kilometers away.