I visited Croatia in September 2021, where I met a Bosnian friend from my master’s program in Zagreb. He showed me around the country before driving us to his home in Bosnia. As a tourist, you have a limited time to discover a country’s culture and history. I pride myself on having excellent priorities when I travel, so the first historic site we visited was Zagreb’s chocolate museum. I ate so much chocolate learned so much about chocolate, and it definitely was a great culinary cultural experience. I wanted to try authentic Croatian food; my friend acquiesced but insisted that we stop by a KFC before leaving the country to get some chicken tenders for his mother. It turns out that, as Bosnia does not have KFC, Bosnians must drive across the border to gain access to this luxurious delicacy.

Zagreb is the capital and largest city of Croatia. The Sava River cuts through it before flowing into the Danube. Zagreb had just enough areas of historic interest to be intriguing, without having so many tourist spots as to be overwhelming. One highlight was an underground tunnel that, it turns out, served as a Yugoslav-era bunker. I was surprised at its length, and how casually accessible it was for people in the city. It was not part of a museum, and we only passed through it to save time when returning to the city center. Although Zagreb is one of the more expensive cities in the Balkan region, for someone who flew in from London, the Croatian prices were a welcome relief.

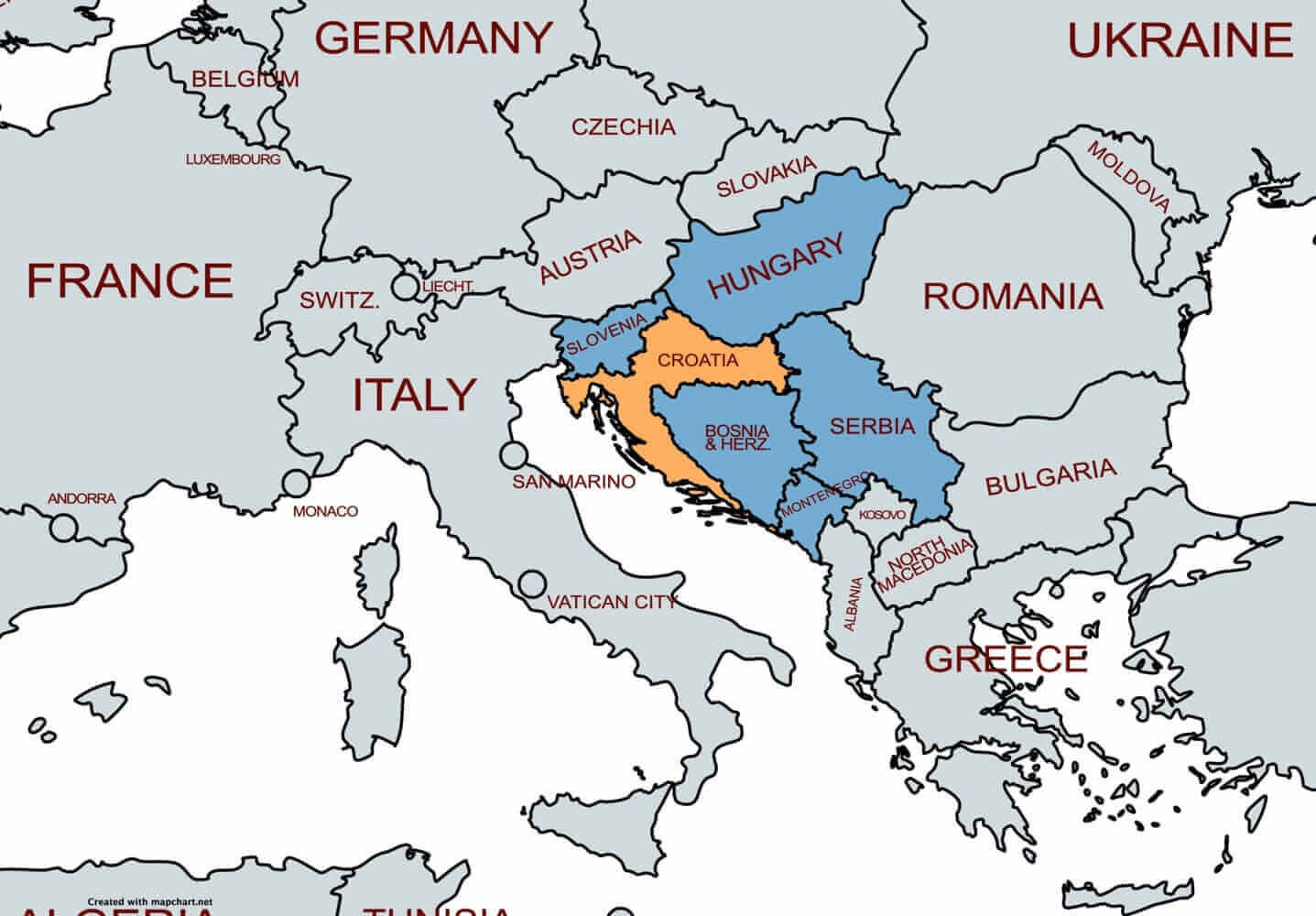

Croatia’s history has been turbulent. From 1102 until 1527, it had a personal union with the Kingdom of Hungary, where the two nations shared the same king but had different governments. During this time, Croatia was at the forefront of battles with the Ottoman Empire, as it expanded its reach into Europe. It joined the Hapsburg Monarchy in 1527, which then evolved into the Austro-Hungarian dual monarchy in 1867. In 1918, after Austria-Hungary was broken up during World War I, Croatia became part of Yugoslavia. During World War II, the nationalist and Nazi-aligned Ustace Croatian movement took control of Yugoslavia, and commenced a genocide against the Serbian minority, Jews, and Romani. They set up concentration camps, including the infamous Jasenovac camp where almost 100,000 people were killed. After the regime was overthrown in 1945, Croatia became part of Yugoslavia once again under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito. As part of Yugoslavia, Croatia had a half century of relative stability during the Cold War.

After Tito’s death, Croatia declared its independence from Yugoslavia in 1991. This angered its Serbian minority, who wanted to remain part of Yugoslavia. Croatian Serbs attempted to create the Republic of Serbian Krajina, with backing from Yugoslavia, to avoid falling under Croat control. The resulting war lasted until 1995, where Croatia managed to reconquer the rebelling provinces, but at a massive cost to its economy and infrastructure. It also involved itself in the Bosnian War by supporting the Croatian Defence Council. Since then, Croatia has sought to integrate itself in Europe by joining the European Union and NATO, and recently the Schengen Area and the Eurozone. I visited Zagreb in 2021 when their currency was still the kuna, however since January 2023 they have started using the euro.

This small village of less than 300 people sits the Croatia-Slovenia border. It has absolutely nothing special to boast of – except for the fact that Tito was born here. Tito led the communist Yugoslav forces that liberated the country from the Independent Croatian State. Many people criticize Tito for being a dictator founded on a cult of personality, and for building up the State Security Administration secret police force (that admittedly was less inhumane than in other communist countries). At the same time, he remains very popular in post-Yugoslav countries due to his ability to keep the nation’s different ethnic groups united and chart an effective non-aligned policy that avoided interference by either the US or the USSR

The Zagreb Cathedral was built in 1217 but was soon destroyed by the visiting Mongols in 1242. In my travels, I have noticed that property damage appears to be positively correlated to Mongol invasions, though I have not yet quantitatively estimated this using a regression. It was rebuilt in Gothic style but was destroyed again in a massive earthquake in 1880. It was rebuilt yet again, this time in neo-gothic style. Then in April 2020 yet another earthquake damaged its spires – hence the scaffolding that prevented me from getting a good shot. At least it was not completely destroyed this time around.

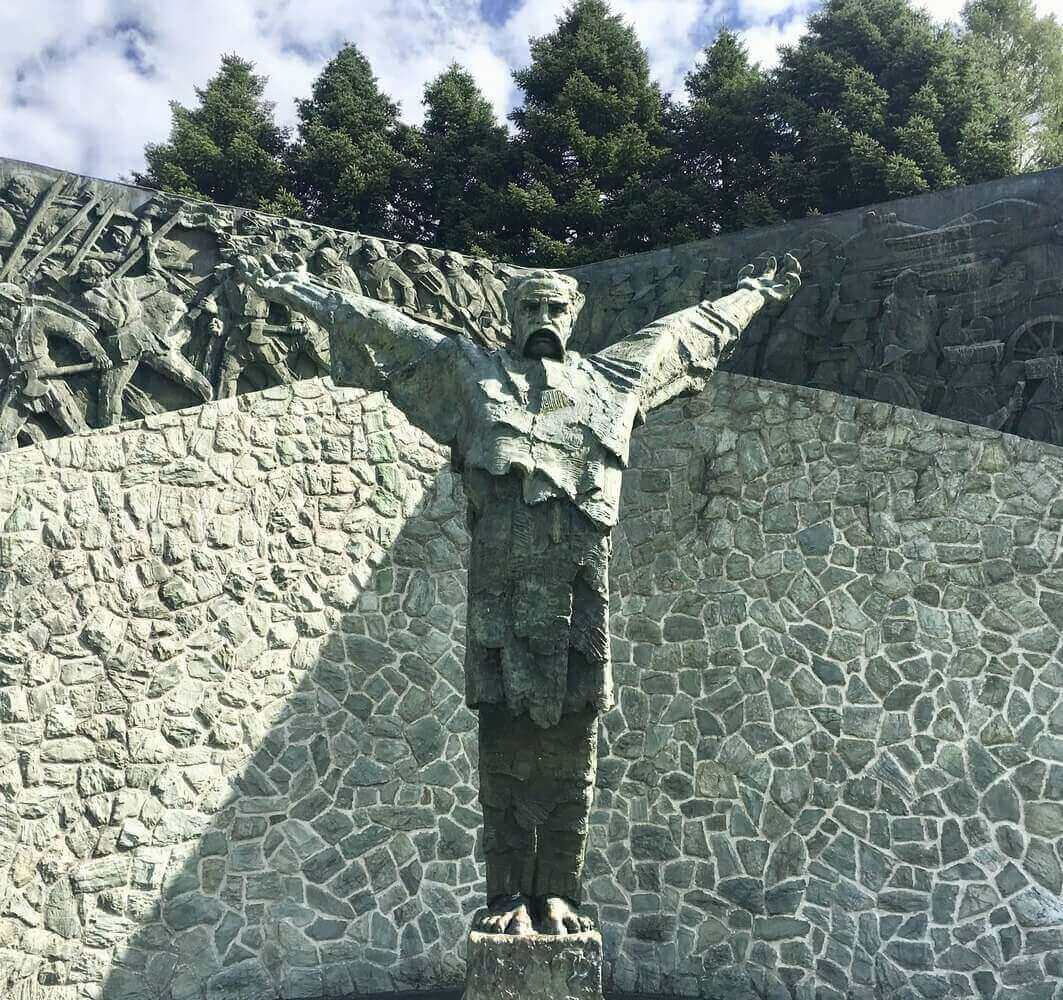

This statue shows Matija Gubec, a Croatian serf who served Ferenc Tahy, a baron renowned for his cruelty. Eventually, the peasants who worked under him had enough, and revolted in 1573. They elected Gubec to be their leader in the Croatian-Slovene Peasant Revolt and hoped to overthrow the nobility. Their valiant effort was short-lived: despite having mobilized over 10,000 people, the peasant army was defeated by the nobles. Gubec was captured, tortured, and executed. Behind the imposing statue of Gubec, a mosaic shows scenes of the battle.